Select the language, please, from the right corner !

Selectați limba dorită, (română), din colțul din dreapta sus !

1 ------------------------

|

Data gathering and analysis to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

Final report

|

Written by ICF February 2021

2 ----------------------------

Disclaimer: The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety

Directorate G — Crisis preparedness in food, animals and plants

Unit G1 — Plant Health

Contact: Thomas Weber

E-mail: SANTE-G1-PLANT-HEALTH@ec.europa.eu

European Commission

B-1049 Brussels

3 -----------------

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

|

Data gathering and analysis to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

Final report

|

Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety February, 2021

4 ------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

Authors

The following people contributed to the writing of this report:

Haines, Rupert (ICF)

Papadopoulou, Liza (ICF)

McEntaggart, Kate (ICF)

Clare, Natalie (ICF)

De Paolis, Simona (ICF)

Fillet, Janne (ICF)

With thanks to the following people for their expert inputs, advice and review provided:

Dr Thomas Geburek

Dr Stéphane Lemarié

Aline Fugeray-Scarbel

5 -------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

|

Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union.

Freephone number (*):

00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11

(*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you).

|

LEGAL NOTICE

This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu).

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2021

ISBN 978-92-76-32484-3

DOI 10.2875/406165

© European Union, 2021

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

6 -----------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

List of abbreviations

|

CSO

|

Civil Society Organisation

|

|

DUS

|

Distinctiveness, Uniformity and Stability

|

|

EC

|

European Commission

|

|

FRM

|

Forest Reproductive Material

|

|

IA

|

Impact Assessment

|

|

IP

|

Intellectual Property

|

|

NCA

|

National Competent Authority

|

|

OCR

|

Official Control Regulation

|

|

PRM

|

Plant Reproductive Material

|

|

RNQPs

|

Regulated non-quarantine pests

|

|

VCU

|

Value for Cultivation and

|

7 -----------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

Table of Contents

Abstract ........................................................................................................... i

Executive summary .......................................................................................... ii

1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 1

2 Context and background .............................................................................. 1

3 Methodology .............................................................................................. 3

3.1 Overarching approach ........................................................................... 3

3.2 Data collection ..................................................................................... 3

3.3 Limitations and gaps in evidence ............................................................ 4

4 Critical analysis .......................................................................................... 5

4.1 Analysis of the problems that would justify updating the existing legislation .. 5

4.2 Technical developments and digitalisation .............................................. 19

4.3 Variation in Member State practices ...................................................... 27

4.4 Synergies with other legislation ............................................................ 31

4.5 The amateur gardener market .............................................................. 34

4.6 Conservation, amateur varieties and preservation seed mixtures ............... 42

4.7 Forest Reproductive Material ................................................................ 51

5 Conclusions .............................................................................................. 59

5.1 Problems with PRM legislation .............................................................. 59

5.2 Synergies with the Plant Health Regulation ............................................ 60

5.3 Synergies with the Official Controls Regulation ....................................... 60

5.4 Technical developments in the breeding sector ....................................... 61

5.5 Digitalisation ..................................................................................... 61

5.6 The amateur gardener market .............................................................. 61

5.7 Amateur, conservation varieties and preservation seed mixtures ............... 61

5.8 Forest Reproductive Material ................................................................ 62

Annexes ........................................................................................................ 63

Annex 1: ICF study matrix ............................................................................... 63

Annex 2: Detailed methodology ........................................................................ 82

Annex 3: List of documents reviewed ................................................................ 86

Annex 4: Targeted survey questionnaires .......................................................... 92

Annex 5: Participants to the surveys by Member State ....................................... 109

Annex 6: Interview topic guide ....................................................................... 112

Annex 7: FRM workshop note ......................................................................... 115

Annex 8: PRM market overview ...................................................................... 126

Annex 9: Forest reproductive material figures .................................................. 130

Annex 10: Validation survey results ................................................................ 139

8 -------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 i

Abstract

The Council has asked the European Commission to carry out a study to assess the options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material (PRM). A supporting research study was contracted to ICF (henceforth “ICF study”).

The PRM legislation (12 Directives covering agricultural, vegetable, forest, fruit and ornamental species and vines) establishes rules for the registration of plant varieties and the certification of seed lots and the production and marketing of seed and other plant reproductive material from these varieties.

The work carried out by ICF provides an updated review and synthesis of evidence available in literature and insights collected from stakeholders on key aspects of the PRM legislation. It:

provides an updated PRM legislation problem analysis, identifying current issues, their drivers and implications;

explores how recent developments, such as technical developments, new regulations (Official Controls Regulation, Plant Health Regulation) and increasing concerns around biodiversity and food security, impact on PRM issues; and

addresses criticisms of previous proposals, by filling gaps in knowledge on the amateur gardener market and addressing Forest Reproductive Material separately.

The ICF study finds that the flexibilities afforded to Member States by the Directives have resulted in a range of differences in how variety registration and PRM certification are administered and implemented. The views of stakeholders on the current policy framework and the way forward are mixed.

9 ----------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 ii

Executive summary

Introduction: The ICF research study (henceforth “ICF study”) set out to collect and analyse data to support a European Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material. The research was undertaken by ICF on behalf of the European Commission’s Directorate General responsible for health and food safety (DG SANTE). The legal framework currently comprises 12 Directives, referred to as the Plant Reproductive Material (PRM) legislation. The Directives (covering agricultural, vegetable, forest, fruit and ornamental species and vines) establish rules for the registration of plant varieties in national catalogues and the certification of seed lots and the production and marketing of seed and other plant reproductive material from these varieties.

Context and background: A proposal from the European Commission in 2013 to simplify and update the PRM legislation and harmonise its implementation across the EU was rejected by the European Parliament and subsequently withdrawn by the European Commission. More recently, the Council1 requested that the European Commission carry out a study on the Union's options to update PRM legislation, and submit a proposal if appropriate in view of the outcomes of the study or otherwise inform the Council of alternative measures.

1 Council Decision (EU) 2019/1905

ICF study objectives: The ICF study builds on earlier works, gathering data with the aim to:

provide an updated problem definition, identify current issues, their drivers and implications for the PRM legislation;

deepen the European Commissions understanding of existing and new issues;

explore how the latest developments, such as technical developments, new regulations (Official Controls Regulation (EU) 2017/625, Plant Health Regulation (EU) 2016/2031) and increasing concerns around biodiversity and food security, impact on the PRM issues; and

address some of the criticisms raised towards earlier proposals, such as filling gaps in knowledge on marketing to amateur gardeners and address issues in relation to Forest Reproductive Material (FRM).

Methodology: A matrix was developed framing the ICF study’s overarching approach to evidence collection and analysis and providing links to the research questions. The data collection combined desk-based research and stakeholder consultation through a programme of selected stakeholder interviews, targeted stakeholder surveys, an online workshop, and a validation survey.

Key limitations in the design of the research and methodologies were: the availability of data with reference to the size of the PRM industry; relatively small-scale field research restricted by budget and a limited timetable (six months); and stakeholder self-selection bias.

Key findings and conclusions

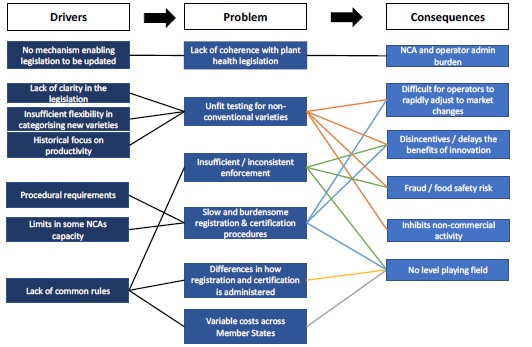

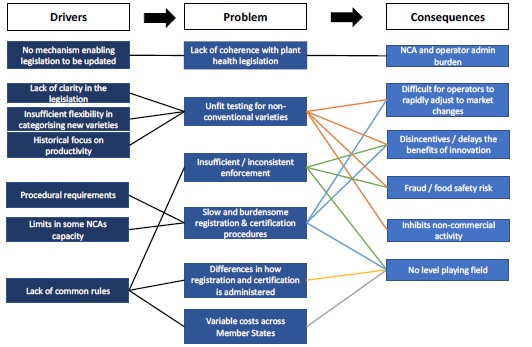

Problems with the existing PRM legislation: Figure 1 provides a simplified overview of the problem analysis, indicating problems identified, their drivers and consequences.

1 Council Decision (EU) 2019/1905

10 -------------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 iii

Figure 1. Simplified problem tree analysis

Drivers

No mechanism enabling legislation to be updated

Problem

Lack of coherence with plant health legislation

Consequences

NCA and operator admin burden

Drivers

Lack of clarity in the legislationInhibits

Insufficient flexibility in categorising new varieties

Historical focus on productivityLimits

Problem

Unfit testing for non-conventional varieties

Consequences

Difficult for operators to rapidly adjust to market changesLack

Disincentives / delays the benefits of innovation

Fraud / food safety risk

Inhibits non-commercial activity

Drivers

Lack of clarity in the legislationInhibits

Insufficient flexibility in categorising new varieties

Historical focus on productivityLimits

Problem

Unfit testing for non-conventional varieties

Consequences

Difficult for operators to rapidly adjust to market

Disincentives / delays the benefits of innovation

Fraud / food safety risk

Inhibits non-commercial activity

Drivers

Procedural requirements

Limits in some NCAs capacity

Problem

Slow and burdensome registration & certification procedures

Consequences

Difficult for operators to rapidly adjust to market changes

Disincentives / delays the benefits of innovation

Fraud / food safety risk

Drivers

Lack of common rules

Problem

Insufficient / inconsistent enforcement

Consequences

Disincentives / delays the benefits of innovation

Fraud / food safety risk

No level playing field

Drivers

Lack of common rules

Problem

Differences in how registration and certification is administered

Consequences

No level playing field

Drivers

Lack of common rules

Problem

Variable costs across Member States

Consequences

No level playing field

The six key problems identified were:

1. There are differences in how registration is administered across Member States. This is a problem, for example, when VCU tests are carried out on agricultural species, in terms of how VCU criteria are interpreted, weighted, and how test results are calculated and assessed, which undermines the EU level playing field.

2. There are differences in how Member States calculate fees (and share costs) for variety registration and PRM certification, which undermines the EU level playing field and can have a potential greater impact on SMEs and non-profit organisations with commercial activities. The lack of common rules in the Directives on how costs are calculated or shared between operators and NCAs results in operators facing different costs for registration and certification in different Member States. Mutual recognition of registered varieties across the EU (through the common catalogues) mitigates the impact of different registration processes to some extent.

3. Testing for conservation and amateur varieties2 and varieties intended for organic production does not appropriately reflect the needs of these varieties, impacting the ability of operators to register new varieties. There is insufficient flexibility in legislative requirements (testing criteria) for these varieties, whilst there is also a lack of clarity in the language and terminology used in the legislation. The use and application of derogations is variable across Member States.

4. The registration process requires time and can be burdensome. However, it is a key safeguard ensuring the quality of PRM on the market. Whilst the legislation permits the transfer of aspects of the certification procedures, under

2 Amateur varieties are varieties with no intrinsic value for commercial production but developed for growing under particular conditions)

11 ---------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 iv

certain conditions, to industry through a system of certification under official supervision, that option is not currently feasible for registration purposes (i.e. DUS and VCU testing). Differences in NCA capacity and performance can result in differences in the time required for registration.

5. There is a lack of coherence between the PRM marketing legislation and the Plant Health Regulation on the issue of regulated non-quarantine pests (RNQPs), resulting in uncertainty for NCAs in terms of which list to consult.

6. Terminology used to describe aspects of the control requirements in the PRM legislation is ambiguous and is interpreted differently across Member States resulting in inconsistent and potentially insufficient control and enforcement. Although for some Member States the flexibility afforded by the Directives is desirable.

Non-harmonised implementation of the legislation:

Key differences identified between Member States related to:

the registration systems of Member States (including the effectiveness of the system, speed and ease of the process, appropriate testing stations etc.). These can impact the decisions made by industry on where to register a variety. The ‘typical’ length of the registration process varies between 1 to 5 years, depending on the species and Member State.

discrepancies in relation to the characteristics used to assess VCU tests. A number of Member States use single key characteristics (especially in species where the yield increase is not very high) to assess VCU tests. Some use an index weighting approach across multiple criteria, while others use a mix of both approaches. In almost all Member States decisions can also be made on the basis of overriding criteria, most frequently linked to high quality varieties or varieties with special characteristics such as high resistance to pests. In most Member States there is no formal inclusion of sustainability criteria in VCU tests.

Member States’ approaches to registering organic varieties, with only a small number having a separate system.

the extent of variety reference collections (ranging from less than 5,000 to over 50,000 varieties) and how they are maintained: most Member States use living variety collections and databases with characteristics and descriptions, although the relative popularity of the methods differs by species.

the cost of registration and technical fees charged for testing. Although cost was not identified as a deciding factor in choosing where to register a variety, it can be a barrier to SMEs and non-profit organisations marketing PRM. Member States also take different approaches to cost recovery: less than half have some system of cost reduction in place for applicants, although in some Member States this is only for conservation and amateur varieties.

the frequency of reporting new registered varieties to the Common Catalogues with timeframes ranging from multiple times per month to once per year.

divergent Member States approaches to control and enforcement.

Synergies with the Plant Health Regulation: There is an overlap between the PRM Directives and the Plant Health Regulation on the issue of regulated non-quarantine pests (RNQPs). Duplication in the listing of RNQPs (albeit with some differences) has resulted in confusion on which list should be consulted by Member States authorities. This has meant additional effort to check both lists and to ensure appropriate application of the legislation. Some Member States argued in favour of a single document listing RNQPs with a preference for that to be the PRM Directives which allows Member States to include the RNQP list in the national regulation. However, some of the pests currently in the PRM Directives were not recommended for listing as RNQPs in the Plant Health Regulation and hence such differences are likely to remain.

12 --------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 v

Synergies with the Official Controls Regulation: The PRM legislation does not fall under the Official Controls Regulation (OCR). Harmonising rules on control across Member States was considered beneficial by the majority of NCAs. Opinion on whether to include the PRM legislation in the OCR was mixed. Arguments in favour of inclusion focussed on the efficiency of implementation (with inclusion in the OCR clarifying and streamlining responsibilities within Member State authorities), and harmonisation in the costs of compliance across Member States. Arguments against valued the flexibility currently afforded by the PRM Directives and highlighted additional complexity and additional burden for NCAs from inclusion of the PRM legislation under the OCR.

Technical developments in the breeding sector: A growing number of New Genomic Techniques (NGT) have emerged, making use of plant genetic information in the breeding process to alter the genome of organisms. Of relevance to the PRM legislation is the extent to which the varieties and PRM resulting from NGTs are accessible to farmers and are subject to the existing registration and certification requirements. There is a need for transparency in how varieties obtained through NGTs are registered and certified, if allowed in the EU.

Digitalisation: In an increasingly digitalised world, there is potential for digital solutions, such as blockchain technology or the use of Digital Object Identifiers (DOI), to improve traceability, and offer greater assurance on the identity, quality and health of seeds, although stakeholders noted that transparency in the sector is improving. Digital illiteracy, poor connectivity and costs remain key barriers in the adoption of such technologies, with a small number of stakeholders also raising concerns over safety, ownership and confidentiality of the information.

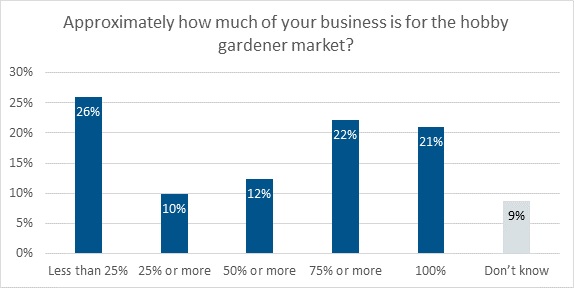

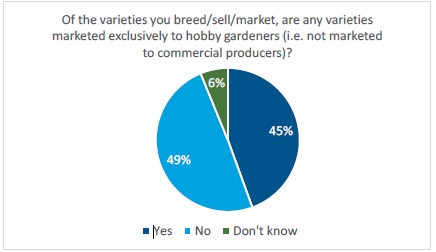

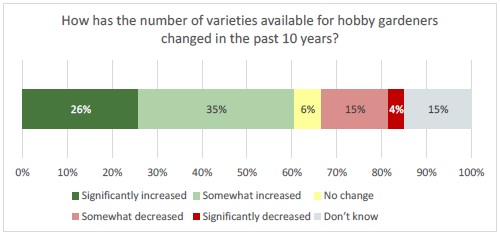

The amateur gardener market: The ICF study engaged maintainers of varieties intended for amateur gardeners (hobby gardeners). The key findings were:

There is mixed evidence regarding the number of varieties available to amateur gardeners, although the ICF study stakeholder survey points to an increase over the past 10 years. This is likely to vary depending on the species.

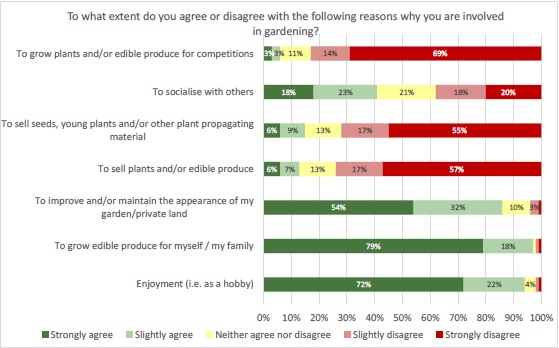

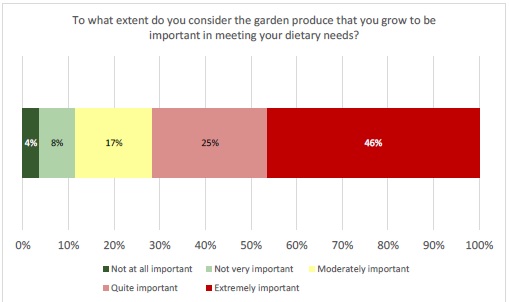

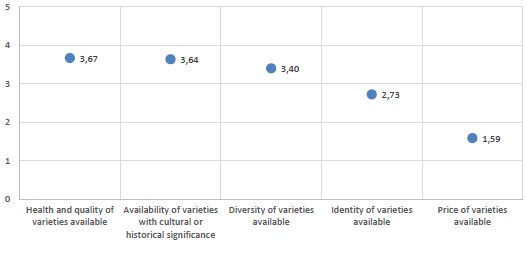

Most amateur gardeners are primarily involved in gardening to grow edible produce for themselves and their families, for enjoyment and to enhance their aesthetic setting. A large number of gardeners also considered produce they grow important in meeting their dietary needs. As a result, their preferences when purchasing PRM differ from those of commercial producers. Amateur gardeners ranked the health and quality of varieties, and the availability of varieties with cultural or historical significance (such as heirloom or conservation varieties) as the most important factors.

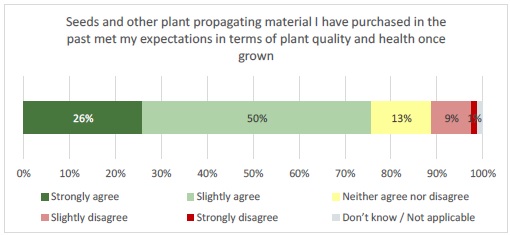

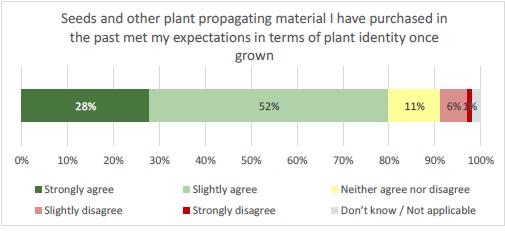

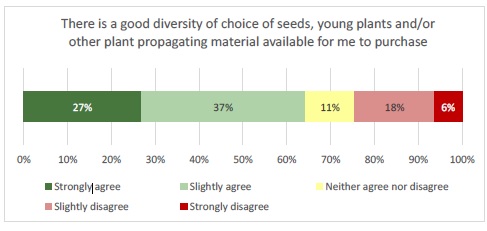

The majority of amateur gardeners suggested that the health, quality and identity of purchased seeds have met their expectations. Some differences existed between Member States. Amongst those who reported encountering problems most referred to plants that did not correspond to the characteristics described on the seed packaging and to bad quality seeds (i.e. low rates of germination). While the majority of amateur gardeners were happy with the diversity of choice available to them, many would like to see greater choice of traditional, regional/local and organic varieties.

A lighter registration regime for varieties intended for amateur gardeners could improve both the availability and genetic diversity of the PRM available to amateur gardeners. However, adopting a lighter regulatory regime for varieties aimed exclusively at amateur gardeners may increase risks to the assurance of PRM identity, quality and health.

Amateur and conservation varieties and preservation seed mixtures: The PRM Directives allow derogations for amateur varieties, conservation varieties and preservation seed mixtures providing lighter market access. Despite this, there is limited use of amateur varieties, conservation varieties and preservation seed mixtures. Key reasons identified were:

13 ---------------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 vi

Low market demand, relatively high production costs and low profitability compared to commercial varieties mean the market is unattractive for commercial companies.

Players involved in the production of native seeds, which are often used in preservation seed mixtures, are typically small-scale, not-for-profit producers Extent to which NCAs and public bodies in Member States encourage registration of conservation varieties and recognise their role in supporting biodiversity conservation.

There were mixed views on whether legal limits on production volumes are in fact limiting the size of the market. However, an expert advisor (member of the researched team) warned that removing the production limits could put conservation and amateur varieties in direct competition with commercial varieties, placing an advantage on the former in terms of varietal registration.

Requirements and costs for registering conservation and amateur varieties differ across Member States, although registration fees are generally lower than for conventional varieties3 and in some cases are zero. Stakeholder views were mixed regarding the limitations imposed by the Directives on the production, maintenance and marketing of conservation varieties to their region of origin with some calling for a more flexible approach. Overall, stakeholders favoured a species-by-species approach to assess the risks related to any relaxation of region of origin rules, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

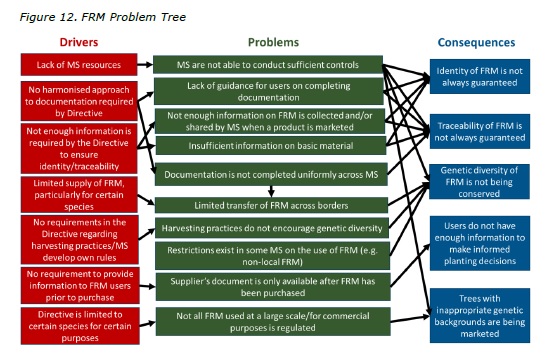

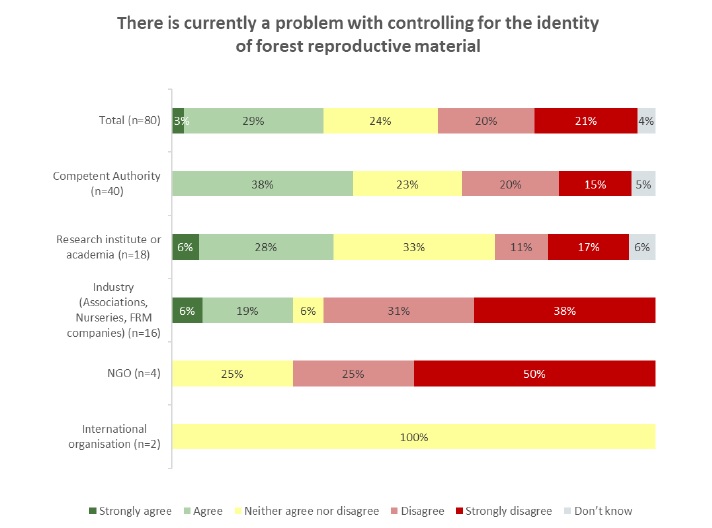

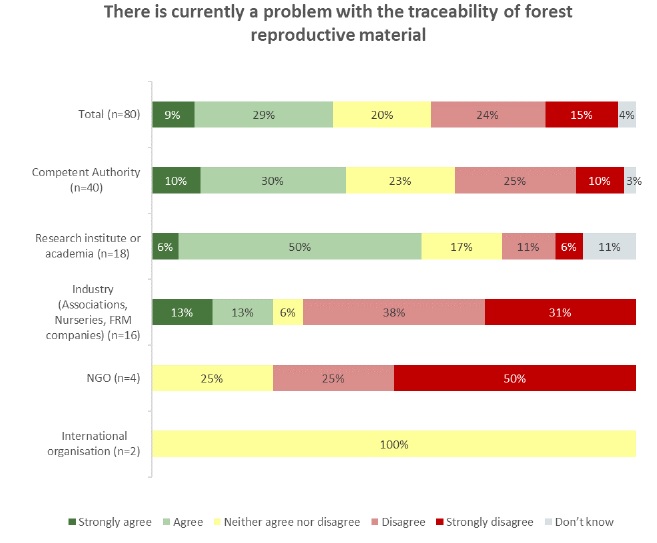

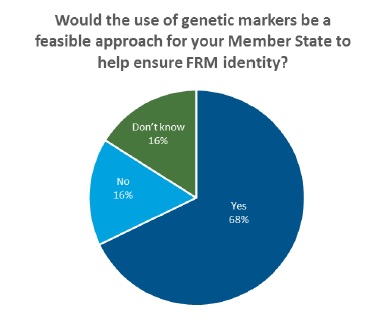

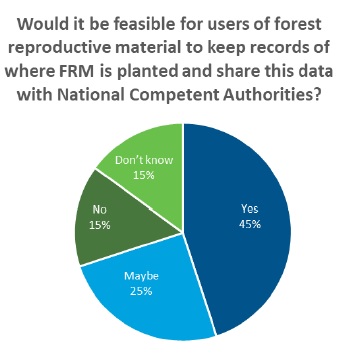

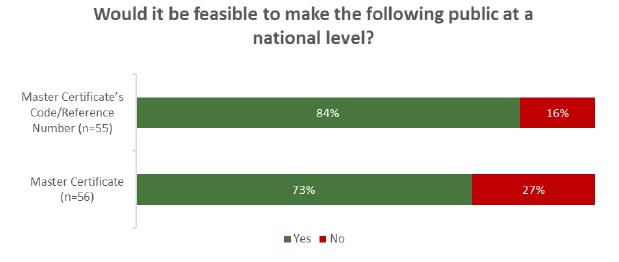

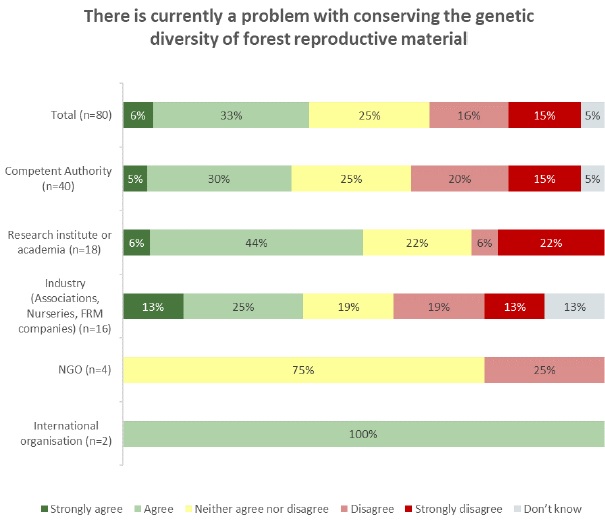

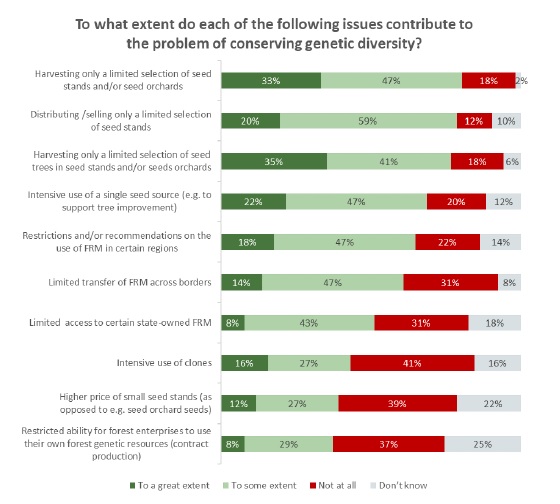

Forest reproductive material: The key problems related to the identity and traceability of FRM, and user information needs. Research institutes and academia constituted the majority of the respondents indicating a problem with the conservation of genetic diversity.

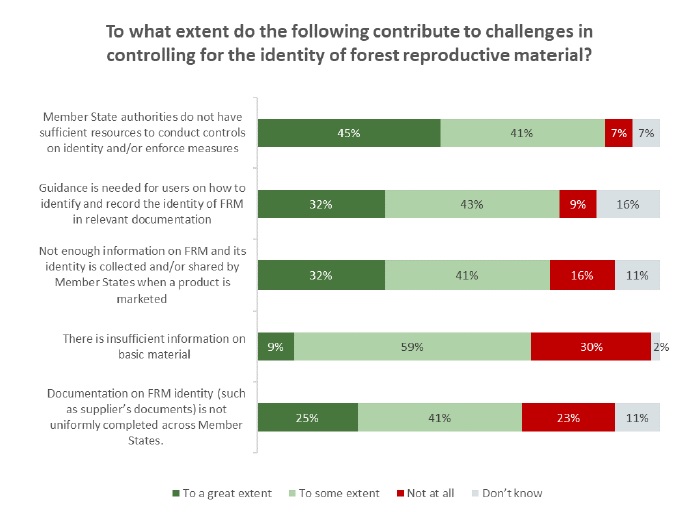

Issues around FRM identity and traceability were caused by the existing levels of control in the production and marketing of FRM. Contributing drivers were:

Insufficient resources in NCAs.

Insufficient guidance on how to identify and record the identity of FRM in relevant documentation.

Insufficient information on FRM and its identity is collected and/or shared when a product is marketed.

Information on basic material could be improved.

Documentation on FRM identity (such as supplier’s documents) is not uniformly completed across Member States.

Suggestions to support increased accountability and improve practices along the production chain and marketing of FRM included: making Master Certificate codes/reference numbers and/or Master Certificates public at a national level; the use of genetic markers; and a voluntary approach to keeping and sharing records of FRM from basic material.

Relating to the problem of the conservation of genetic identity in FRM, the following main drivers were identified:

Harvesting and distribution of seed stands.

Intensive use of single seed source.

Limited transfer of FRM across borders.

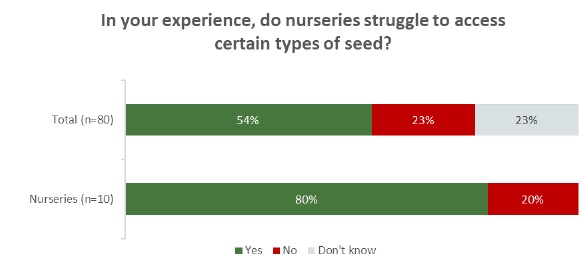

In addition, around half of all stakeholders identified access to state-owned FRM and access to certain types of seeds as drivers.

3 The term ‘conventional varieties’ is used in this report as an encompassing term of varieties that are registered through the normal process of DUS and VCU testing. It refers to commercial production of varieties usually bred for high input agriculture, as opposed to, for instance, conservation and amateur varieties, preservation seed mixtures etc.

14 --------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 vii

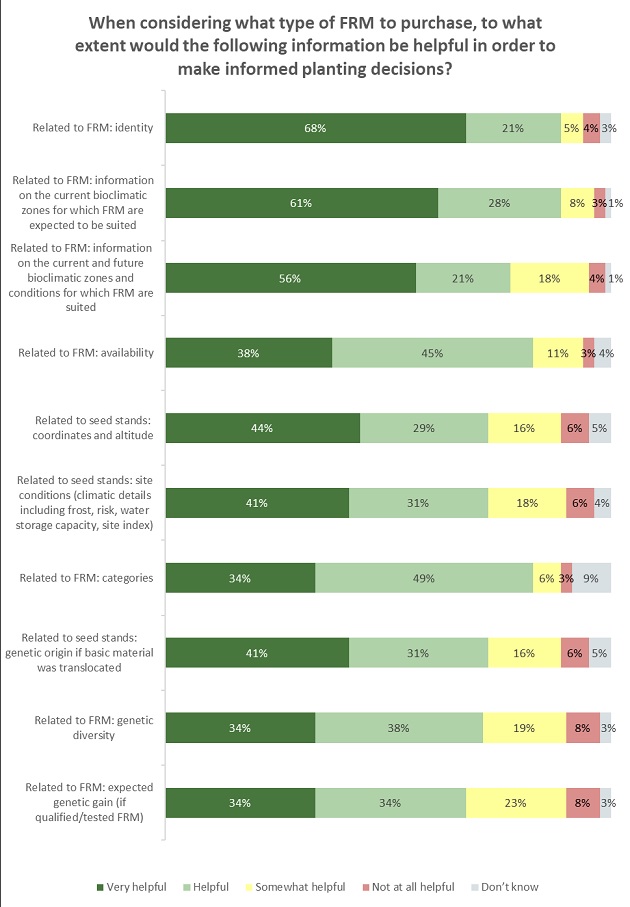

Relating to the user information needs, stakeholders stated that the most useful information for users of FRM would be:

Information on FRM identity;

Deployment zones, ideally considering both current and future bioclimatic zones and conditions for which FRM are suited or expected to be suited for;

Information on genetic diversity of FRM; and

Information on FRM availability.

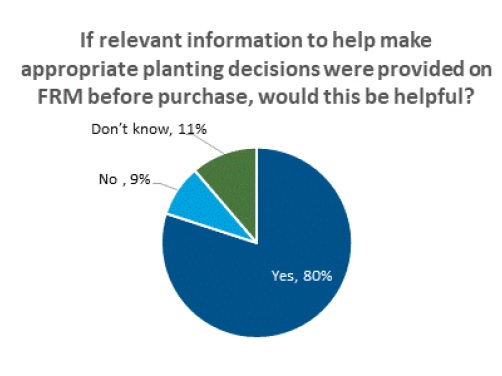

Whilst supplier’s documents contain the left level of information, they would benefit from harmonisation across the EU. Further, stakeholders indicated that in order to inform decisions on choosing appropriate planting materials the above-mentioned information would be helpful if provided in advance of purchase.

15 ---------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 1

1 Introduction

This Final report is the final deliverable under the ICF study “Data gathering and analysis to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material (PRM)” (henceforth “ICF study”), as contracted by the European Commission’s Directorate General in charge of health and food safety - DG SANTE. This ICF study was commissioned by the European Commission (DG SANTE) in June 2020 and was undertaken by ICF, supported by a team of experts.

This report incorporates feedback received from the Commission on the Interim and Draft reports as well as additional evidence collected through the ICF study’s ‘validation survey’. The remainder of the report is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the context and background to the ICF study.

Section 3 presents the methodology, including details on the specific data collection approaches and any methodological limitations.

Section 4 presents a critical analysis of the ICF study research questions, drawing on the collected evidence, including:

Section 4.1 on problems relevant to the production and marketing of PRM, their drivers, how they evolved in the past years, their scale, stakeholders impacted and the potential for simplification of the existing legislation.

Section 4.2 on the latest technical developments and the potential benefits and risks of digitalisation.

Section 4.3 on the need for EU level action to address issues.

Section 4.4 on synergies between plant reproductive material legislation and other legislation, including a discussion on any likely inefficiencies.

Section 4.5 on the amateur gardener market structure and latest trends, motivation for amateur gardeners and issues experienced, including a discussion on any limitations linked to the existing variety registration system.

Section 4.6 in relation to conservation, links to the Habitats Directive and the use of conservation, amateur varieties and preservation seed mixtures.

Section 4.7 on forest reproductive material, including a discussion on current problems, user information needs, barriers and likely solutions.

Section 5 presents the conclusions from the ICF study.

2 Context and background

The marketing of seeds is a critical and strategic issue. It is currently discussed in Europe as a lever not only for supporting the European agricultural sector, which historically has been a major objective of the EU, but also to address increasing public and policy concerns over sustainability, biodiversity and food security.

The marketing of seeds has been a topic for EU action and legislation for decades. The legal framework comprises 12 Directives - henceforth referred to as the PRM legislation. Key features in this framework are the mandatory variety registration4 and, for agricultural species, certification of seed lots. There have been discussions in the past to address the shortcomings and gaps of that legal framework, as well as its simplification, which eventually led to a proposal from the Commission in 2013. That proposal was rejected by the European Parliament. In 2014, the Council then invited the Commission to put forward an updated and amended proposal. By Decision (EU) 2019/1905, the Council has requested that the Commission should submit a study on the Union's options to update the legislative framework on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material by 31 December 2020.

4 The only exception from mandatory variety registration are ornamental plants (Council Directive 98/56/EC).

16 ------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 2

The Commission study builds on the rejection of the 2013 proposal by the European Parliament, and the request from the Council to the Commission to revisit the issue and put forward a revised proposal. Yet, in the decade that has passed since the earlier studies several developments call for a revised outlook, including:

market developments in the PRM industry – particularly technical innovation such as the use of blockchain technologies and new genomic techniques;

changes in legislation in the food and plant health sector;

challenges in food security exacerbated by climate change;

increasing concerns over sustainability and biodiversity;

new regulations (Official Controls, Plant Health) that have recently entered into force and their relationship to PRM; and

concerns voiced by Member State authorities with reference to the implementation of the existing legislation on PRM.

A number of the issues identified in 2013 have remained at the heart of the debates between stakeholders and Member States. As the seed industry grows in value and there is a trend towards greater market concentration (including notable recent mergers such as the Bayer-Monsanto merger completed in 2018; Bonny, 2017; Lianos, 2019; OECD, 2018), concerns remain over the extent to which the current EU framework might favour those Member States and businesses with an important stake in the production and marketing of conventional varieties (e.g. Louwaars et al., 2009). Annex 8: PRM market overview presents an overview of the PRM market structure, size, stakeholders and latest trends.

Public and stakeholder concerns over biodiversity and the state of the environment more broadly, already considered at the time of the 2013 proposal, have grown significantly to become a leading issue on the policy agenda of many Member States and the EU. This is embodied in the European Green Deal, the EU Biodiversity Strategy (which includes as an objective the full integration of biodiversity consideration into other EU policies; EC, 2020) and the Farm to Fork strategy adopted in 2020. Meanwhile, further developments in EU legislation have posed questions on potential overlaps, tensions or, rather, lack of integration between the EU legal framework for PRM and new legislation. For example, the new EU Plant Health Regulation (2016/2031) overlaps with PRM Directives on the issue of Regulated Non-Quarantine Pests (RNQPs), while the expansion of the Official Controls Regulation (2017/625) offers a potential model for more effective monitoring and enforcement practices.

Meanwhile, there has been much civil society and research activity around conservation varieties, organic production, and addressing the challenges of climate change across food production, horticulture, and forest management. That, together with EU and state sponsored experimentation, has contributed to enriching the pool of knowledge and ideas that inform the current debate on PRM and Forest Reproductive Material (FRM) in the EU.

Criticisms were raised by various stakeholders as a result of the earlier work that supported the 2013 proposal. Amongst those, a public campaign from civil society criticized the Commission for helping larger companies, putting undue burdens on a small and niche sector5 and limiting the choice of plant varieties available on the seed market. Issues were also noted by national authorities and breeders in their everyday work with variety registration and certification. Further, some gaps and challenges were identified in the work to develop the previous proposal, including a lack of engagement and understanding of the amateur market (marketing to hobby gardeners), with the views of home gardeners being one of the gaps. Marketing to home gardeners was not addressed in the 2013 evaluation and Impact Assessment and there is a lack of

5 By niche sector, this report refers to plant reproductive material that is “marketed in small quantities by non-professionals or microenterprises” (European Parliament, 2013a)

17 ----------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 3

understanding and robust data on home gardeners’ preferences and needs regarding PRM.

This study provides the opportunity to address criticisms raised towards earlier work and update the problem definition in order to inform and support the Commission’s study on the European Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of PRM. The ICF study provides an updated problem definition. It builds on earlier findings, strengthening and revising them where needed, identifies the current issues for stakeholders and how these have evolved since 2013, and deepens the Commission’s understanding of existing and new issues. It is also a first step towards engaging stakeholders on the issue, to help address criticism to earlier work.

3 Methodology

This section outlines the principles and rationale underpinning the data collection (Section 3.1); provides a summary of the methods used for data collection including an overview of the quantitative and qualitative data collected (Section 3.2) and; an overview of any gaps and data limitations and an assessment of the impact of these issues in the ability of the data to provide a sound basis for responding to the ICF study research questions (Section 3.3).

3.1 Overarching approach

The approach to data collection was developed based on the: ICF study aims and objectives, as confirmed in the project Kick-off meeting; background to the study, including past criticisms and existing sensitivities; evidence base, as well as identified gaps in data; broad landscape of stakeholders with an interest in PRM; challenges of engaging stakeholders during the ongoing Covid-19 crisis.

The approach also benefited from ICF’s experience in designing robust research tools and independent expert advice on specific aspects of the research and the most appropriate data collection methodologies.

The ICF study matrix in Annex 1: ICF study matrix identifies how each of the research tasks described below link to the research questions.

3.2 Data collection

The approach to data collection (summarised in Table 1) combines desk-based research and an extensive stakeholder consultation through interviews, an online workshop with FRM experts, targeted online surveys and a validation survey.

|

Data collection

|

Description/Objective

|

Stakeholders engaged

|

|

Desk-based research

|

Scientific data and research, peer reviewed academic literature, grey literature (reports, working papers), industry reports and EU institutions’ policy documents and studies, were reviewed ensuring that the ICF study built on existing evidence, adopted informed approaches to the stakeholder consultation and offered a representative/objective view of the key issues.

|

NA

|

|

Interviews

|

Interviews carried out with a selection of stakeholders explored stakeholders’ views on challenges in the production and marketing of PRM including underlying drivers, recent developments in the PRM sector and their impacts (positive or

|

40 interviews with academics, civil society organisations, public authorities

|

18 -------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 4

|

negative); and advantages and disadvantages of alternative requirements.

|

industry representatives and farmers’ organisations

|

|

Online workshop

|

A workshop with FRM experts on issues around the production and marketing of FRM, the conservation and use of forest genetic resources and the genetic diversity of FRM.

|

6 FRM experts

|

|

Targeted surveys

|

with regulators and competent authorities collected evidence on the implementation of the Directives at a national level

with amateur gardeners collected evidence on amateur gardeners’ motivation for gardening; how they source PRM and the key considerations in the purchase of PRM; and concerns or issues around the use of PRM.

with maintainers and marketers of registered varieties provided an understanding of the number and types of varieties on the EU market aimed exclusively at hobby gardeners

with FRM stakeholders tested the findings and recommendations emerging from the FRM workshop.

|

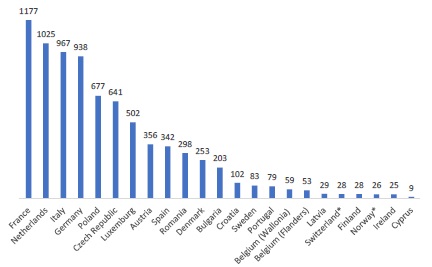

27 countries, 25 Member States

6,089 amateur gardeners from 29 countries

81 maintainers of registered varieties for the amateur market

80 users of FRM and national competent authorities

|

|

Validation survey

|

Tested the emerging findings of the ICF study (except on FRM) with stakeholders. The results informed the conclusions.

|

88 stakeholders across categories

|

| |

|

|

|

3.3 Limitations and gaps in evidence

The following limitations relate to the design of the research and methodologies employed and evidence available:

Data availability: There was limited publicly available data with reference to the size of the PRM industry. Available data was difficult to aggregate or compare as it often used different metrics to describe the seed market in monetary (e.g. value of sales, market share, revenue etc.) or other terms (e.g. production volumes), rarely offering a breakdown by agricultural sector, Member State or species. Recent literature further suggests the data available are likely to underestimate the size and value of the market, while some metrics viewed in isolation may offer a distorted view of the sector (Jansen et al., 2019; Bonny, 2017).

Sample size: The findings are based on a relatively small-scale field research of 40 interviews and four stakeholder surveys. The ICF study aimed to engage interviewees across categories, which imposed further restrictions in the numbers of stakeholders engaged per category. The diverse nature of stakeholders suggests that the aggregated views of participants presented in this report may not necessarily represent all stakeholders in the sector or even within each category.

Self-selection bias: Stakeholders for the field research were identified with support from the European Commission and key stakeholders disseminating a call for participation in the research. Participation, particularly in the surveys, was a result of stakeholders coming forward to express their interest.

Political sensitivities and strong stakeholder views: The subject of the ICF study is a highly politicised one with many stakeholders representing different

19 -------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 5

industries and interests. Responses collected indicated that there may be differences in opinions between stakeholders on what problems and drivers are most relevant and important, depending on their perspective and often knowledge. Sometimes such differences were also recorded within the same type of stakeholder. This was addressed by triangulating evidence sources, identifying differences in opinions and explaining those, to the extent possible, so that findings faithfully represent the views of stakeholders.

4 Critical analysis

This section presents analysis and findings against the ICF study research questions, drawing on the different sources of evidence.

4.1 Analysis of the problems that would justify updating the existing legislation

This section presents the main problems in the sector related to the legislation of PRM, as well as suggestions for how these problems could be addressed through changes to the legislation. It responds to research question 1 and research questions 1a to 1f. Figure 1 provides a simplified overview of the problem analysis.

Figure 1. Simplified problem tree analysis of the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

Drivers

No mechanism enabling legislation to be updated

Problem

Lack of coherence with plant health legislation

Consequences

NCA and operator admin burden

Drivers

Lack of clarity in the legislationInhibits

Insufficient flexibility in categorising new varieties

Historical focus on productivityLimits

Problem

Unfit testing for non-conventional varieties

Consequences

Difficult for operators to rapidly adjust to market changesLack

Disincentives / delays the benefits of innovation

Fraud / food safety risk

Inhibits non-commercial activity

Drivers

Lack of clarity in the legislationInhibits

Insufficient flexibility in categorising new varieties

Historical focus on productivityLimits

Problem

Unfit testing for non-conventional varieties

Consequences

Difficult for operators to rapidly adjust to market

Disincentives / delays the benefits of innovation

Fraud / food safety risk

Inhibits non-commercial activity

Drivers

Procedural requirements

Limits in some NCAs capacity

Problem

Slow and burdensome registration & certification procedures

Consequences

Difficult for operators to rapidly adjust to market changes

Disincentives / delays the benefits of innovation

Fraud / food safety risk

Drivers

Lack of common rules

Problem

Insufficient / inconsistent enforcement

Consequences

Disincentives / delays the benefits of innovation

Fraud / food safety risk

No level playing field

Drivers

Lack of common rules

Problem

Differences in how registration and certification is administered

Consequences

No level playing field

Drivers

Lack of common rules

Problem

Variable costs across Member States

Consequences

No level playing field

This section analyses each of the problems identified in Figure 1 in turn using the following structure:

Overview of the problem

The drivers of the problem

The stakeholders affected and the size of the problem

Evolution of the problem, particularly since the 2013 Impact Assessment (IA)

Addressing the problem and the potential for simplification of the legislation Differences in how

220 --------------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 6

4.1.1 Variable costs across Member States

4.1.1.1 Overview of the problem

The registration of new varieties, the certification of PRM and the mutual recognition of registration between countries (through the European common catalogues) are key features of the current regulation on PRM. Common catalogues are compiled by the Commission on the basis of national catalogues and list the varieties of agricultural and vegetable species, fruit plants and vine propagating material that can be marketed in the EU.

Before registration, a new variety's identity is tested for: Distinctness; Uniformity; Stability (DUS testing); and Value for cultivation and use of the variety (VCU testing, for agricultural crops). Certification and inspections guarantee the identity, health and quality of seeds and propagating material before marketing. Whilst DUS tests are the same among countries for a given species, this is not the case for VCU, with some countries requiring more intense field testing and hence higher costs, or that testing is conducted on a wider number of characteristics (falling under the four VCU criteria or additional to those). Additional characteristics may also be tested on demand of the breeder. Data provided by Member States through a survey of NCAs indicates that there are differences in the fees charged by different Member States6 and how those fees vary between species or between different types of operator. As a result, operators in different Member States face different costs for registration, which prevents the achievement of an EU-wide level playing field in the sector.

4.1.1.2 Main drivers of the problem

The main driver of this problem is that there are no common rules in the Directives7 on how fees for registration and certification should be calculated and charged or how costs should be shared between operators and NCAs. As such, Member States employ different systems, based on their understanding of how costs should be shared and what the cost structure should incentivise (e.g., whether it should incentivise biodiversity, reduce burdens on SMEs or place a higher societal value on certain species).

4.1.1.3 Who the problem affects and the size/scale of the issue

The different fees may affect different stakeholders: registration costs typically affect plant breeders, whereas certification costs affect seed producers and distributors, which are likely to differ from the breeder depending on the species8.

Both the review of past documents and the new evidence indicates that SMEs and not-for-profit organisations selling PRM at low margins are the most affected by this issue.

These types of applicants may lack the resources to anticipate and cover registration and/or certification costs. Numerous stakeholders (including NCAs involved in controls, certification and registration, farmer organisations, users and organisations representing breeders and suppliers of PRM) have highlighted how the current regulation largely underestimates the disproportionate burden that certification and variety registration imposes on SMEs and non-profit organisations with commercial activities. Some (particularly industry stakeholders) have noted how the current registration system favours larger commercial enterprises while limiting consumer choices and penalising smaller actors. As noted by one Civil Society Organisation interviewee, those who wish to register and/or certify varieties already face burden and indirect costs associated with navigating the administrative system. As such, the direct costs, on top

6 44% of participants to the validation survey agreed there are differences impacting the EU level playing field, compared to 22% who disagreed (see Annex 10)

7 65% of participants to the validation survey agreed, compared to 10% who disagreed

8 Generally these differ for self-pollinated species.

21 ----------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 7

of the indirect costs and burden of registration and/or certification, may act as a barrier or a disincentive to such applicants.

This also affects operators in niche segments with lower margins and where demand for uniformity is lower (such as those selling to amateur gardeners). As described by some respondents to the survey of operators involved in the amateur gardener market (i.e. maintainers survey), the costs of registering a variety and, where applicable, certifying seed lots cannot be justified in some cases in these niche markets. This then impacts the operator’s decision to market that variety, particularly in cases where operators are dealing with a high number of varieties with relatively low turnover per variety. On the other hand, the current variety registration system provides a level playing field for operators of all sizes: varieties of large and small companies are objectively compared next to each other and are subject to the same testing regime.

For larger operators, industry interviews suggest that costs and the differences in costs between Member States do not pose a significant burden or problem. Larger operators may in fact see an opportunity in such differences and choose to register varieties in countries where the cost of registration is lower – an option that may not be available to SMEs in the sector. This would be a consideration for NCAs who may wish to apply more stringent VCU standards. Unless such standards are adopted by other Member States, they could lead to operators opting to register varieties in Member States with lower standards.

The differences in how Member States have managed to regulate the administrative burden to operators mean that this problem affects operators in some Member States more than others. For example, some Member States have a cost responsibility sharing framework in place, whereby the costs of registration and certification are split between the private and the public sector. Some Member States, such as the Netherlands, consider company size and turnover when calculating fees. Other Member States do not take these factors into consideration.

Although many stakeholders mentioned this as an issue across the consultation activities conducted, evidence on the actual scale or extent of this problem is limited.

4.1.1.4 How the problem has evolved since 2013

The problem was identified in the 2013 IA. The comparison between the reviewed documents (dated 2008-2014) and the ICF study stakeholder consultations did not reveal significant change in the nature of the problem. However, changes in factors external to the legislation, such as new technical developments (e.g. new genomic techniques) and increased concentration in the market may contribute to additional burdens and pressures on operators. Considering the above, the relative significance of this issue (i.e. the differences in costs of registration and certification) may have increased, particularly for SMEs.

4.1.1.5 Potential for updating and simplifying the existing legislation

Existing legislation could be amended to provide clearer guidance to Member States on costs and cost sharing, reducing the variability between Member States. The 2013 revision proposed options for the EU-wide adoption of ‘full cost recovery’ for registration and certification, meaning that operators would be responsible for covering the full cost of registration and certification. This addressed the problem driver by establishing rules for the calculation of costs, which would create a common approach across Member States and hence a more level playing field for the sector.

However, the proposed solution was not well received by industry stakeholders, in part because it has the potential to generate unintended consequences. Key issues were:

It would disincentivise registration, because of the increased cost of doing so;

It would unfairly place 100% of the burden on industry;

registration and certification is administered

22 ------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 8

It would place a disproportionate burden on SMEs, who are less able to subsume additional costs into their business, giving unfair competitive advantage to larger operators; and

These issues could result in a reduction in the registration of new varieties, and a less competitive marketplace, ultimately leading to reduced consumer choice.

There may be other options for the Commission to issue rules or guidance for how the costs of registration and certification should be calculated, reflecting the disproportionate burden placed on SMEs and not-for-profit organisations. Such rules or guidance could also reflect the impact of higher and variable costs on niche markets and on the incentives to develop and register varieties in less profitable but ecologically important species. The previous proposal to provide a full exemption in costs for all SMEs was rejected, as explained in the report from the Presidency to the Council following the rejection to the previous proposal on the grounds that “a block exemption would create market distortions”. It further noted:9

“If the scope of the Regulation is clear (professional and non-professional users) and there is simplified access to the market for certain types of plant reproductive material, then a reduction of costs for micro-businesses and individuals could be achieved. Moreover, consideration could be given to alternative measures to reduce costs.” (p. 6)

4.1.2 Differences in how registration and certification is administered

4.1.2.1 Overview of the problem

Evidence collected through the survey of NCAs and interviews with stakeholders indicates that there are differences between Member States relating to the implementation and functioning of the legislation. Differences in costs (see Section 4.1.1) is one aspect. Another is the difference in how registration and certification is administered.

One element of the process, DUS testing, has been harmonised. Stakeholders indicated that harmonised DUS tests are necessary to ensure clarity and to avoid overlap with other regulations and inconsistencies between Member States. Harmonised DUS tests also help keep costs down and facilitate their administration both for Member States and operators. However, differences in DUS testing between Member States remain, notably regarding the management and composition of variety reference collections.

The conduct of VCU tests (relevant for agricultural species) differs significantly between Member States10 and sometimes depending on the crops, in terms of which characteristics are examined, how results of VCU tests are calculated and assessed, as well as how long tests take. Most countries use some type of scoring system for calculating VCU results across the four VCU criteria. However, the specific characteristics assessed can differ (especially with reference to factors in the physical environment and pest resistance) and the application of weighting means that “a good characteristic can outweigh a lesser result in another characteristic”11. Criteria are usually further specified according to the species examined (e.g. Greece). Overriding criteria and differences in the assessment depending on the crop type can also apply. For instance, in Estonia, for varieties for which yield is more than 105% of the standard variety, quality is not important. At the same time, when assessing winter cereals the most important characteristic is winter hardiness.

9 Council of the European Union (2014). Report 10618/14. Available online at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10618-2014-INIT/en/pdf

10 44% of participants to the validation survey agreed, compared to 20% who disagreed (see Annex 10 for detailed results)

11 NCA survey response Member States

23 -------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 9

There are also differences in how Member States incorporate sustainability criteria and how organic varieties are assessed (discussed in 4.3).

4.1.2.2 Main drivers of the problem

The Directives allow Member States significant flexibility in how they implement and administer the certification and registration process. With regard to registration, Commission Directive 2003/90/EC sets out the four criteria Member States should use for VCU testing12, but Member States determine how the criteria are implemented, VCU results are calculated and how these criteria are considered. They also determine how any additional criteria should be included (e.g. sustainability criteria) and how the system is applied for different production systems (e.g. organic varieties).

Differences in the administration of the registration and certification process are also influenced by institutional differences between Member States, such as how departments and agencies are organised, and competencies split within a Member State.

These differences may also be influenced by different policy environments and priorities in different Member States. This may influence, for example, the extent to which sustainability criteria are included in the calculation of VCU results.

Registration and certification within a Member State can also be managed by different competent authorities. For instance in France, the Ministry of Agriculture supported by a Technical Committee for Plant Breeding and the French Variety and Seed Study and Control Group (CTPS and GEVES)13 are responsible for variety registration and the official service for control and certification of seeds and plants (SOC)14 is responsible for seed certification.

4.1.2.3 Who the problem affects and the size/scale of the issue

Mutual recognition of registered varieties across the EU (through the common catalogues) mitigates to some extent the impact of different registration processes by Member States, since a breeder can choose the country of registration where the process is easier and/or less costly and then sell the variety across the EU. This option may not be available for SMEs.

Interviewed stakeholders across groups expressed concerns over the lack of harmonisation and consequent lack of an appropriate level playing field in the internal EU market. It was the problem most frequently identified by industry stakeholders, with eight out of thirteen industry interviewees highlighting the issue. These stakeholders noted that the lack of harmonisation impacts the efficiency, cost, administrative burden and ease of producing and marketing varieties in the EU. How these differences manifest is discussed further in Section 4.3.

Beyond the impact on the level playing field, these differences could also affect the environmental impact of the Directives. CSO organisations interviewed expressed concerns that the Directives place too strong an emphasis on productivity, at the expense of biodiversity and the development of other traits beneficial to long-term food security. Information provided by NCAs indicate that most Member States continue to place the highest priority on yield when calculating VCU results. However, approaches do differ. Some Member States include additional sustainability criteria or place a higher value on other criteria. This means the potential contribution of the registration system to long-term sustainability goals also likely differs by Member State. PRM regulations

12 (1) Yield, (2) Resistance to harmful organisms, (3) Behaviour with respect to factors in the physical environment, and (4) Quality

13 https://www.geves.fr/about-us/the-ctps/

14 https://www.gnis.fr/en/soc-official-service-for-control-and-certification-of-seeds-and-plants-in-france/#:~:text=SOC%20(official%20service%20for%20control,in%20application%20of%20French%20regulation.

24 ------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 10

offer a way to incentivise innovation on criteria of societal interest that the market insufficiently values.

4.1.2.4 How the problem has evolved since 2013

This issue was identified in the 2013 IA. In the consultation following the IA, several stakeholders noted that the degree of non-harmonisation was underestimated. Differences related to sustainability criteria and the approach to registering organic varieties have likely increased since 2013, as these issues have become increasing policy priorities.

4.1.2.5 Potential for updating and simplifying the existing legislation

The 2013 IA and following proposal put forward a potential solution of simplifying the legislation from 12 directives to one regulation. This would help to harmonise implementation, as a regulation allows for less Member State interpretation as compared to directives. This was criticised at the time due to a “one-size-fits-all” approach not being fit for all types of PRM nor country specifics. Some stakeholders consulted as part of the ICF study touched on this, with some expressing interest in a transition to a regulation, but with most others indicating that a degree of flexibility remains important.

Additional guidance and clarity in the directives regarding VCU testing, the incorporation of sustainability criteria and the approach to organic varieties could help to address this problem. The extent to which this is justified remains unclear: although it is apparent from stakeholder feedback that there is a problem, the evidence available does not allow for this problem to be quantified.

4.1.3 Practical conditions set out for testing are unfit for some varieties

4.1.3.1 Overview of the problem

The marketing directives were first established in 1966 and 1971. Originally, the scope of the legislation was agricultural crops and a limited number of other species (cereal seed, beet seed, fodder plant seed, seed potatoes and forest reproductive material). Changes in today’s markets and the addition of other crops to the scope of the legislation mean that aspects of the legislation (such as on testing and certification of varieties) are no longer adequate.

The application of the testing required under the legislation can result in operators having to adhere to requirements that do not accurately portray the needs of conservation and amateur varieties or the preservation seed mixtures. A majority of stakeholders responding to the 2013 IA consultation recognised that amateur and conservation varieties in particular should not be under the same regulations as other PRM categories. This includes members of Civil Society Organisations, Farmers associations, industry stakeholders and NCAs. Under the current legislations, derogations exist only for some categories of varieties.

4.1.3.2 Main drivers of the problem

There are three main drivers of unfit registration, DUS and VCU testing and certification conditions:

The historical focus of the legislation on commercial agricultural crops and varieties.

A lack of flexibility in the specific requirements of the legislation.

The lack of clarity of terms used in the directives.

The historical focus of the marketing directives was on improving the productivity of agricultural crops, quality for further processing (e.g. bread production) and on resistance to biotic and antibiotic stress (EC, 2013). Hence, the focus was on commercial agricultural crops and vegetatively propagated material. The criteria set for registration, DUS and VCU testing and certification are mostly modelled on the needs of these commercial crops/materials. However, stakeholder interviews reveal that the needs for

25 ------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 11

some crops and varieties – including conservation amateur and varieties destined for organic production, differ greatly from other varieties. For example, satisfaction of criteria on uniformity does not apply to organic varieties suitable for organic cultivation, which values seeds that are less homogeneous. Another example provided is that of landraces, which can be low yield and are unable to compete with high productivity varieties (particularly cereals). As such, for some of these varieties, criteria that are not relevant or are inappropriate must be applied. CSOs in particular emphasized the impact of this on producers who practice low-input agriculture with a focus on locally adapted characteristics (such as climatic resistance), maintaining diversity, reducing environmental impact etc.

This reflects the different needs of two distinct communities of users; commercial producers and a growing community of ‘diversity’ farmers whose interest is only semi-commercial and their primary objective is to maintain and improve genetic diversity with productivity being secondary (expert advisor input).

Interviewees (NCAs and industry stakeholders) indicated that the directives are inflexible. Where requirements laid down in the legislation are found to be inappropriate for a particular variety, NCAs or operators are not able to change those requirements to make them more appropriate. This inflexibility manifests in two ways. Firstly, the standing committee cannot edit the main body of the Directives, meaning that requirements laid down in the basic legislation cannot be changed. Secondly, a new variety cannot be allocated to the best fitting category, but must be allocated to the category identified through the existing standards for classification. For example, one industry stakeholder expressed interest in registering their special seed-propagated fruit variety within the seed-propagated vegetables, as the criteria were more fitting, but this was not permitted.

There is lack of clarity over many of the terms used in the directives. Derogations are permitted under the legislation, with lighter regimes applied for certain varieties, such conservation and amateur varieties. These are implemented by Member States. However, ambiguity in language and definitions (e.g. ‘commercial use’, ‘region of origin’) used in the legislation mean that there are differences in how the legislation is interpreted, and how lighter regimes are implemented, across Member States. This issue was raised by industry stakeholders, NCAs and CSOs. Similarly, several stakeholders highlighted how the scope for the certification process is unclear for fruit material, which has different requirements to other plant reproductive materials.

4.1.3.3 Size/scale of the issue and most affected stakeholders

Inappropriate conditions can affect the time, costs, and ability of operators to get new varieties registered and certified. If varieties are not registered and plant reproductive material (seed) are not certified they cannot be marketed. The same DUS testing, as for variety registration, is necessary for obtaining plant variety protection15.

Overall, the most directly impacted stakeholders are breeders and suppliers of varieties, especially those that do not fit in the standard categories of the 12 Directives, such as conservation, amateur, varieties intended for organic production. The direct impact is in the extra costs and administrative burden (including on NCAs) involved in following

15 Plant variety protection refers to the granting of intellectual property (IP) lefts to the breeder of a new variety. IP lefts also known as the Plant Breeder lefts (PBR) are lefts granted to the breeder of a new variety of plant that give the breeder exclusive control over the propagating material and harvested material of a new variety for a number of years. There are two exemptions in relation to this type of IP left. The breeder’s exemption allows breeding for non-commercial purposes and for the purpose of discovering and developing other varieties. The agricultural exemption allows farmers to use the product of their harvest with regard to EU-protected varieties, as propagating material under strict and defined conditions.

26 --------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 12

requirements that would not be necessarily incumbent to certify the quality of the variety.

This reduces operators’ incentives to develop new varieties and may reduce the flow of innovation in the market. Several organisations representing organic breeders and breeders of traditional, heritage, local and conservation varieties and producers of preservation seed mixtures mentioned this as a substantial limitation in their activities. The issue also affects amateur gardeners who may wish to register their own varieties but are discouraged by the administration and costs. Any reduction in market innovation has the potential to impact on both consumer choice and wider biodiversity and conservation objectives. It was suggested that the DUS criteria in particular are a hurdle to maintenance and further development of biodiversity because they are designed to benefit varieties bred for use in commercial food and feed processing.

Derogations are available for conservation varieties, amateur varieties as well as for preservation seed mixtures. However, these derogations do not cover all varieties that they may be appropriately applied to and vary in their application across Member States16. In addition, derogations come with their own marketing restrictions, such as quantitative limits on production (see Section 4.6).

Interviews revealed that NCAs are aware that the issues can in some cases discourage registration of varieties that do not fit well with the criteria. If varieties are not registered, they cannot be marketed. This is a particular concern for traditional varieties (popular in the amateur market) which risk being lost if they are not registered and hence available for marketing. CSOs stated that DUS criteria, developed for agricultural crops, have wrongly been applied to all types of seeds, including native seeds and amateur varieties17. One CSO also noted that derogations for preservation mixtures should be extended to apply beyond fodder plant seed mixtures.

Unregistered varieties are sometimes sold illegally on the black market. This can create further issues as authorities cannot control and regulate variety distribution and use. This creates further burdens on NCAs in the long run.

Ambiguity in the language and terminology used in the legislation makes it difficult to determine whether a new variety should be subject to the registration process, or should be registered using a lighter regime for conservation and amateur varieties. NCA interviewees indicated that this creates an incentive for operators to argue for varieties at the margin to be registered using the lighter regime. One NCA representative indicated that the lighter registration regime for amateur varieties can leave room for fraud, as producers may be inclined to register varieties as amateur even if they do not fall into that category to avoid do incur costs (the registration of amateur varieties are in many cases free of charge). The extent of concern regarding this issue varied across Member States. Fraudulent activity, and business conducted via the black market, have the potential to generate food safety, economic and environmental sustainability issues.

Finally, differences in the use of derogations and application of lighter registration regimes across Member States impacts on the level playing field at the EU level.

16 Two CSOs noted that the scope of Directive 66/401/EEC could be expanded, with one specifying it could helpfully include mixtures for intermediate and subsidiary crops, flowering plants, green manure, flower strips, cereal-legumes mixtures, and variety mixtures. (Interviews with CSOs)

17 The term ‘amateur variety’ is used in this report as defined in Directive 2009/145 to mean “a variety of vegetable species with no intrinsic value for commercial crop production which is developed for growing under particular conditions and is contained within a National List” https://www.legislation.gov.uk/nisr/2011/38/made/data.xht?view=snippet andwrap=true

27 ------------------------

Data gathering to support a Commission study on the Union’s options to update the existing legislation on the production and marketing of plant reproductive material

February, 2021 13

4.1.3.4 How has the problem evolved since 2013

The comparison between the 2013 IA and the most recent evidence indicates that the problem remains a concern for most stakeholders. Some recent developments indicate that the problem may have become more acute since 2013.